Client Suggestions at BuildingConnected

Building for builders

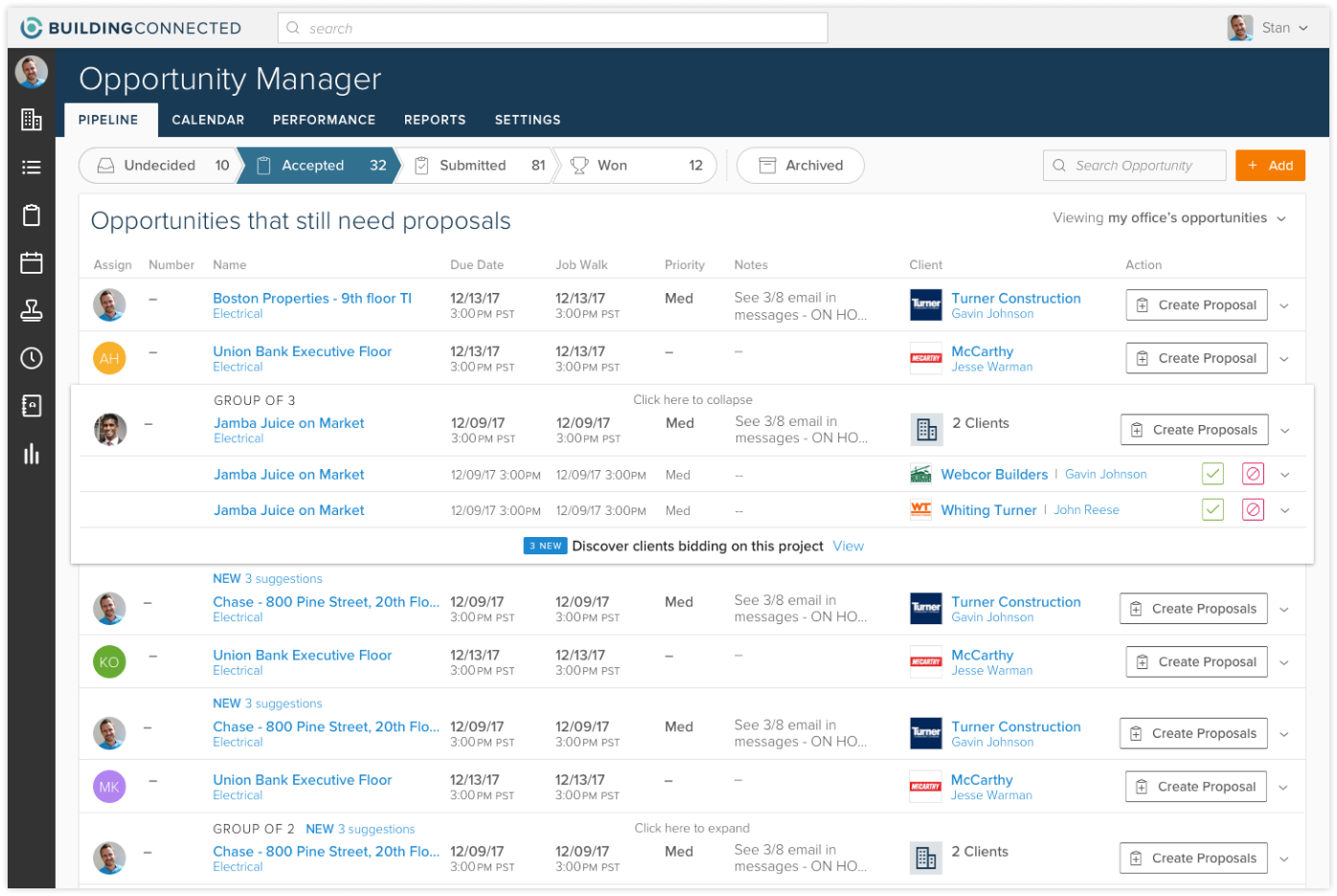

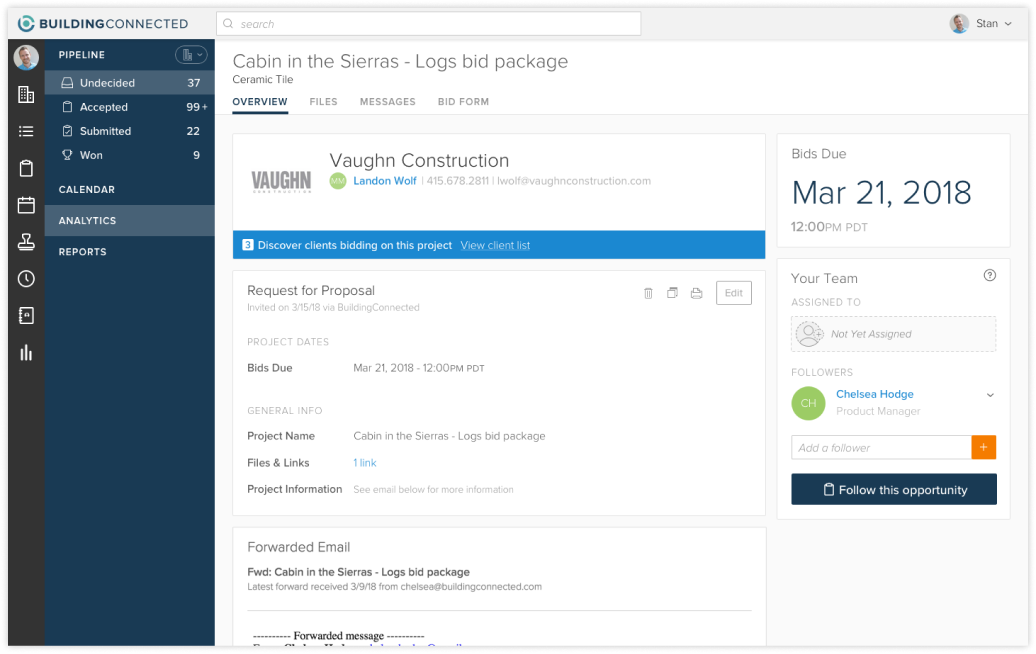

BuildingConnected’s Bid Board product is built primarily for subcontractors, specifically estimators and bid-coordinators. Their job is to handle a high volume of invites from general contractors. They must carefully read through project files, determine whether an opportunity is worth their time, and submit a bid in hopes of landing new business.

Keeping a healthy pipeline of projects is critical to their business and choosing to compete for the wrong project can mean many wasted person-hours. But even a great bid-proposal can be rejected for reasons outside of their control.

The problem

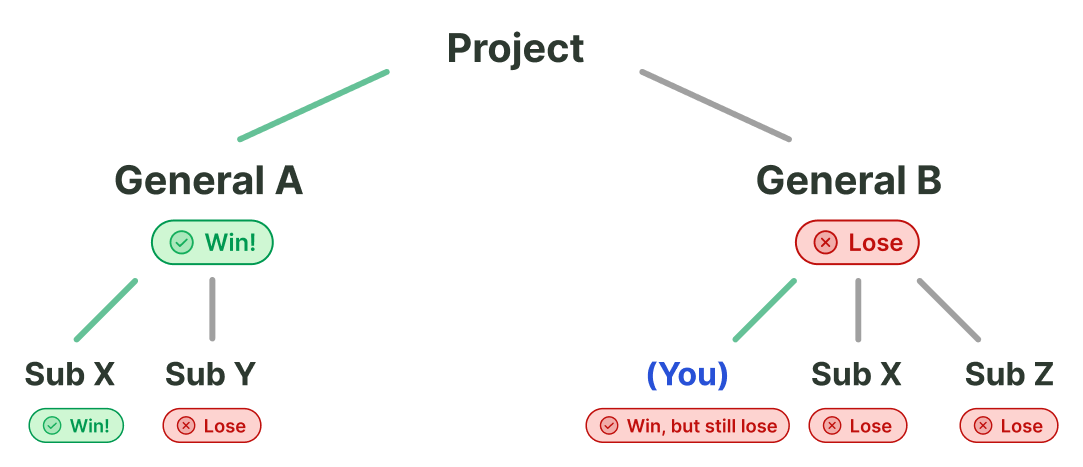

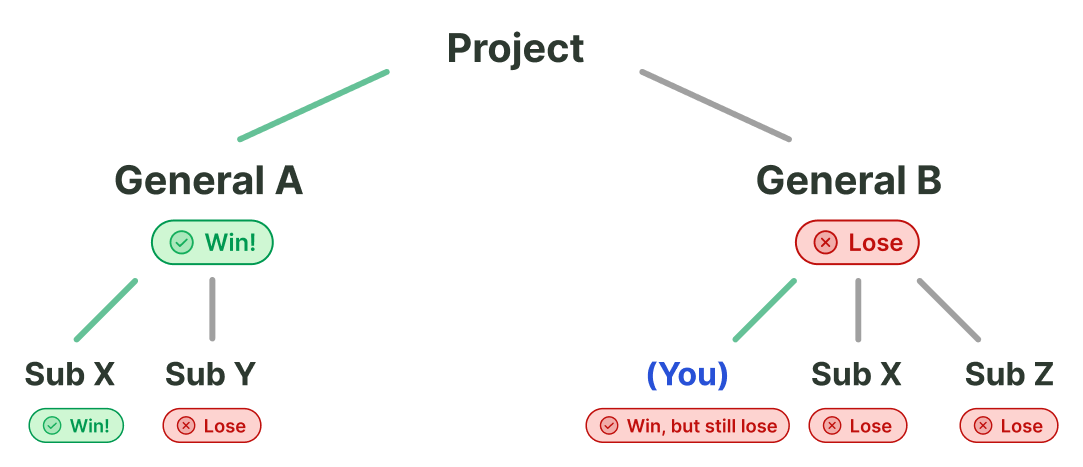

In many cases, the general contractor who sent an invite is not the only company working on the job. They may be competing with another GC to win the contract from the property owners. The sub is a step removed from the ultimate decision-maker.

Construction is a heavily relationship-based business. Companies tend to do business with those that they’ve worked well with in the past. If a general contractor you don’t know bids on a project, they might not invite you.

Subs can then end up in a frustrating situation: they’ve done the hard work and submitted a great proposal, but if the general contractor who invited them loses, then so do they.

Thus, in order to maximize their chance of winning, subs want to send their bid to every general contractor in the running. But if they don’t know everyone who is bidding, how can they?

A solution, an opportunity

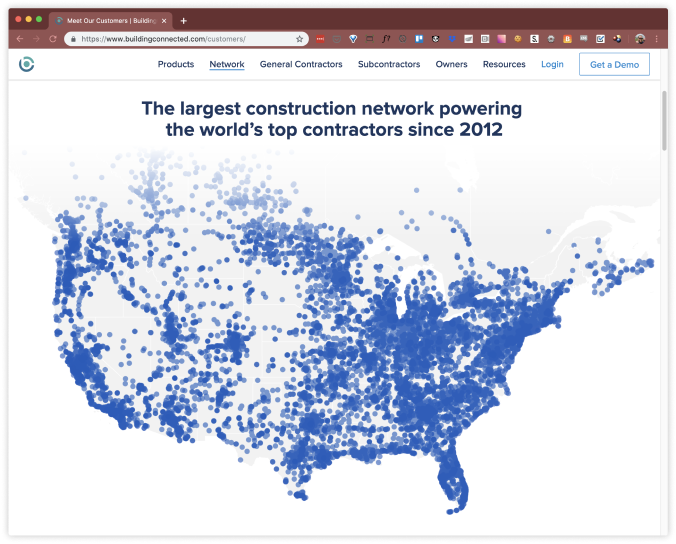

The power of BuildingConnected’s platform is the ability to aggregate project data from an entire city or region. Through the use of machine learning, BuildingConnected can form associations between invites and reliably determine when two general contractors are competing for the same project. This information can be be passed on to subcontractors, so that they can submit to all parties and thus maximize their winning potential.

Our product team knew this was a potential value-add. The question for us was: how do we surface it?

Rapid prototyping

I was assigned to develop an experience for surfacing suggestions to subcontractors. Our data could tell when another GC was bidding, but how could we communicate this? Would subs understand the point? Also, how would they react?

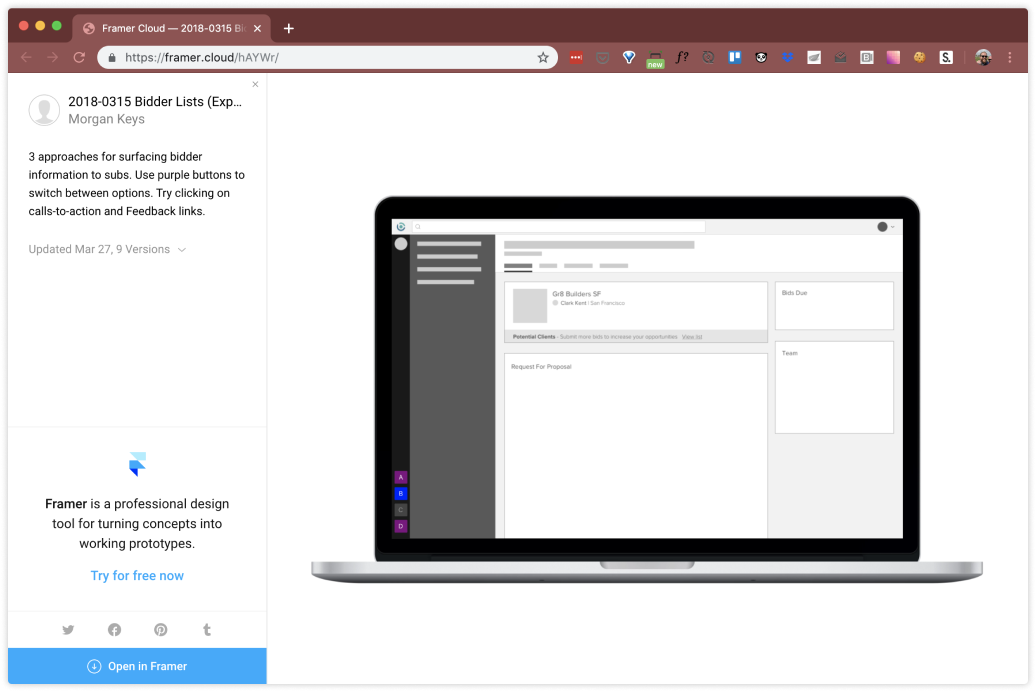

We had a short time-frame to work with and only enough resources for a small experiment. I began sketching concepts and quickly had three approaches.

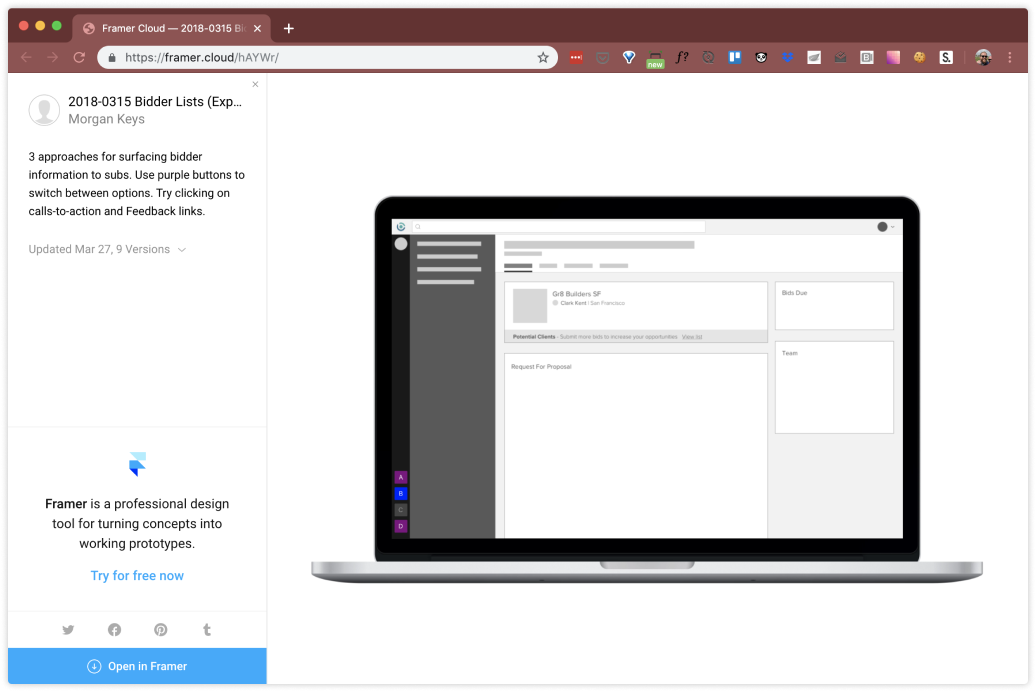

I am a big believer in high-fidelity interactions, and I love the power of tools like Framer to create more realistic experiences. I decided to build rough but interactive Framer prototypes for feedback and quickly tested three options with members of our sales and customer success teams.

Designing for learning

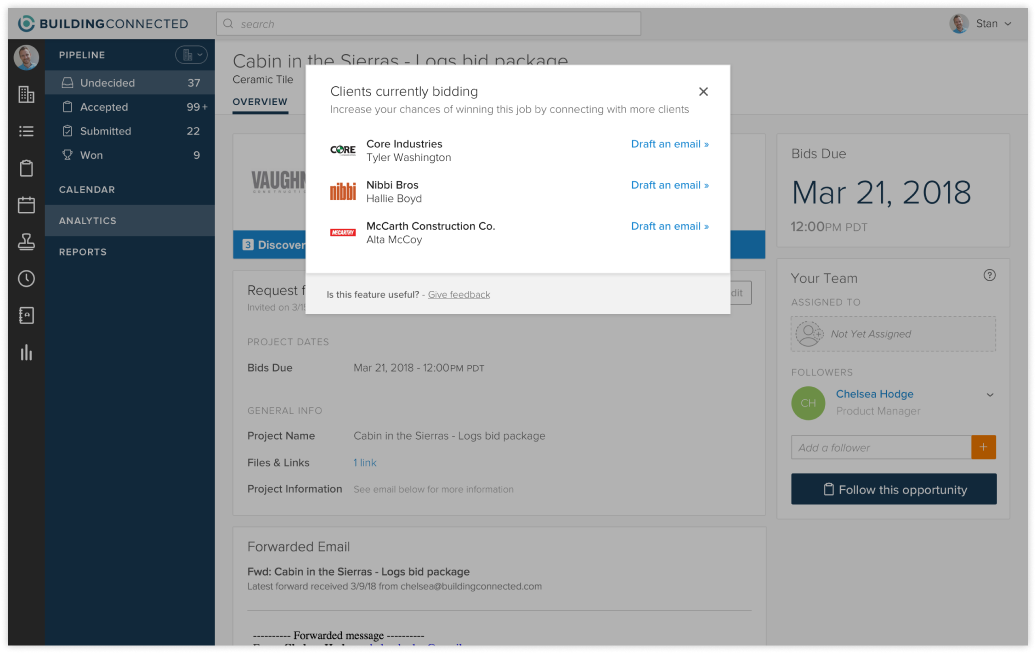

Initial feedback suggested that a combination of two approaches would be best. I built a high-fidelity prototype to work out the details of styling and placement.

Product intended this project to be a quick experiment—only enough to gauge interest. With this in mind I tried to build in a way that could maximize learning.

We couldn’t build a sophisticated flow, but I designed the experience to include mail-to links so that users could at least have a call-to-action to decide on—these clicks could then give us quantitative data to support interest.

I also included a feedback form in the primary modal. The idea was that if subs needed different information, or if they disliked our suggestions, they could let us know immediately.

The ultimate sign of success would be if users wanted to see our suggestions and take action on them.

Initial impact

The feature was very successful. During the trial period, we collected FullStory sessions (reconstructed videos based on mouse and click data). We watched a user discover the feature and then furiously double-check every opportunity in their extensive backlog for more suggestions.

Product and Customer Success also reported postive feedback from conversations with users. The feature definitely had traction.

However, there were two important learnings:

- Users seemed reluctant to use the mail-to links

- Users wanted all of the suggestions at once

A constantly evolving product

Part of the need for a quick release on our first pass was due to incoming features that would significantly change the UI we were designing for—we were going to have to redesign anyway.

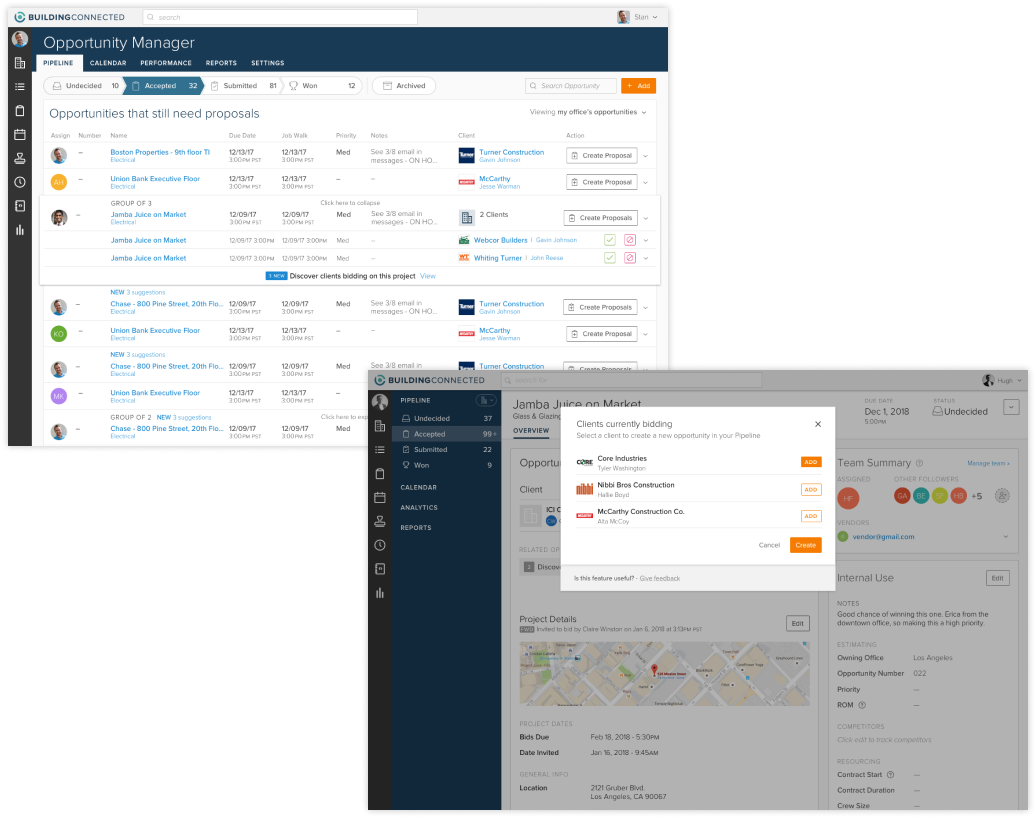

For our second pass we took advantage of the richer functionality. Users now had the ability to group opportunities together. Building off of this:

- I designed calls-to-action for the inbox, allowing users to quickly scan for new suggestions

- Instead of mail-to links, I designed a quick-add feature so that users could stay in the same workflow and effortlessly begin tracking the new general contractor

Ongoing impact and learnings

Client Suggestions had a significant impact on the Bid Board product and BuildingConnected. It became a strong selling point for our Sales team and helped drive revenue until the company’s eventual acquisition.

Personally, I also learned an important lesson about about my own thinking and process. As a designer, I think there is often an urge to avoid solutions that increase “clutter”—the concern being aesthetics and scanability. However, in this case, adding more information to the already dense inbox was still the right choice. Ultimately, “clutter” must be handled holistically so that we can stay focused on the task at hand.

Morgan Keys | Summer 2019

Client Suggestions at BuildingConnected

Building for builders

BuildingConnected’s Bid Board product is built primarily for subcontractors, specifically estimators and bid-coordinators. Their job is to handle a high volume of invites from general contractors. They must carefully read through project files, determine whether an opportunity is worth their time, and submit a bid in hopes of landing new business.

Keeping a healthy pipeline of projects is critical to their business and choosing to compete for the wrong project can mean many wasted person-hours. But even a great bid-proposal can be rejected for reasons outside of their control.

The problem

In many cases, the general contractor who sent an invite is not the only company working on the job. They may be competing with another GC to win the contract from the property owners. The sub is a step removed from the ultimate decision-maker.

Construction is a heavily relationship-based business. Companies tend to do business with those that they’ve worked well with in the past. If a general contractor you don’t know bids on a project, they might not invite you.

Subs can then end up in a frustrating situation: they’ve done the hard work and submitted a great proposal, but if the general contractor who invited them loses, then so do they.

Thus, in order to maximize their chance of winning, subs want to send their bid to every general contractor in the running. But if they don’t know everyone who is bidding, how can they?

A solution, an opportunity

The power of BuildingConnected’s platform is the ability to aggregate project data from an entire city or region. Through the use of machine learning, BuildingConnected can form associations between invites and reliably determine when two general contractors are competing for the same project. This information can be be passed on to subcontractors, so that they can submit to all parties and thus maximize their winning potential.

Our product team knew this was a potential value-add. The question for us was: how do we surface it?

Rapid prototyping

I was assigned to develop an experience for surfacing suggestions to subcontractors. Our data could tell when another GC was bidding, but how could we communicate this? Would subs understand the point? Also, how would they react?

We had a short time-frame to work with and only enough resources for a small experiment. I began sketching concepts and quickly had three approaches.

I am a big believer in high-fidelity interactions, and I love the power of tools like Framer to create more realistic experiences. I decided to build rough but interactive Framer prototypes for feedback and quickly tested three options with members of our sales and customer success teams.

Designing for learning

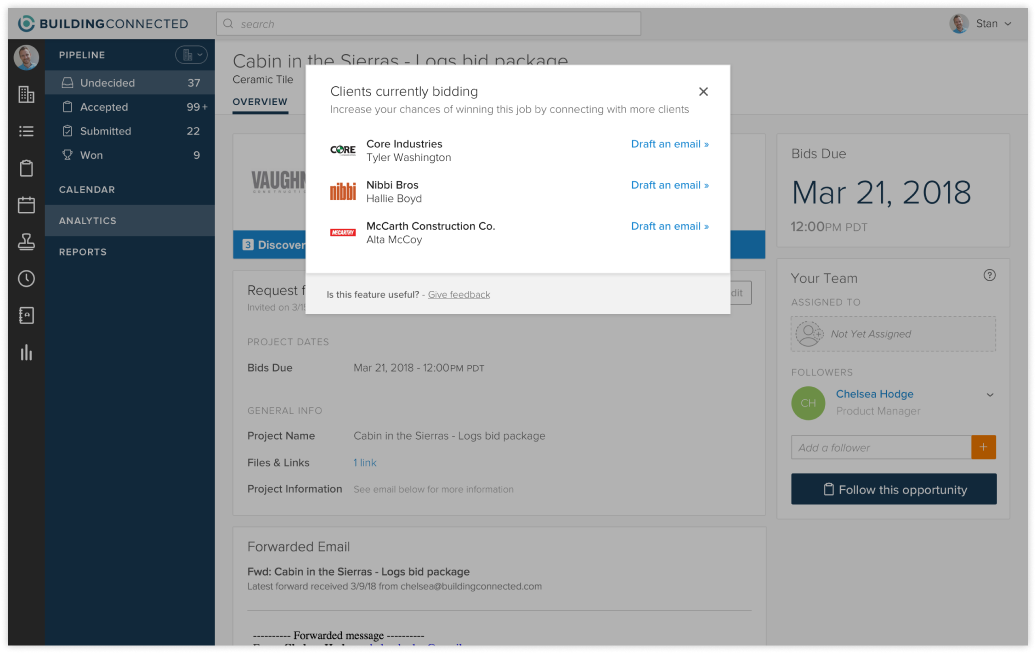

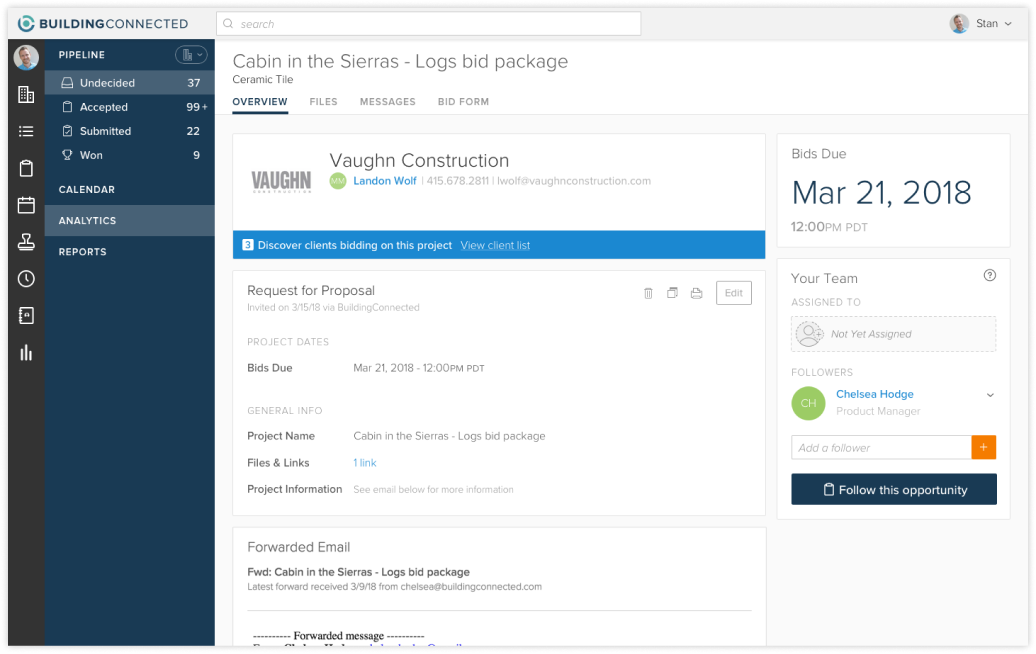

Initial feedback suggested that a combination of two approaches would be best. I built a high-fidelity prototype to work out the details of styling and placement.

Product intended this project to be a quick experiment—only enough to gauge interest. With this in mind I tried to build in a way that could maximize learning.

We couldn’t build a sophisticated flow, but I designed the experience to include mail-to links so that users could at least have a call-to-action to decide on—these clicks could then give us quantitative data to support interest.

I also included a feedback form in the primary modal. The idea was that if subs needed different information, or if they disliked our suggestions, they could let us know immediately.

The ultimate sign of success would be if users wanted to see our suggestions and take action on them.

Initial impact

The feature was very successful. During the trial period, we collected FullStory sessions (reconstructed videos based on mouse and click data). We watched a user discover the feature and then furiously double-check every opportunity in their extensive backlog for more suggestions.

Product and Customer Success also reported postive feedback from conversations with users. The feature definitely had traction.

However, there were two important learnings:

- Users seemed reluctant to use the mail-to links

- Users wanted all of the suggestions at once

A constantly evolving product

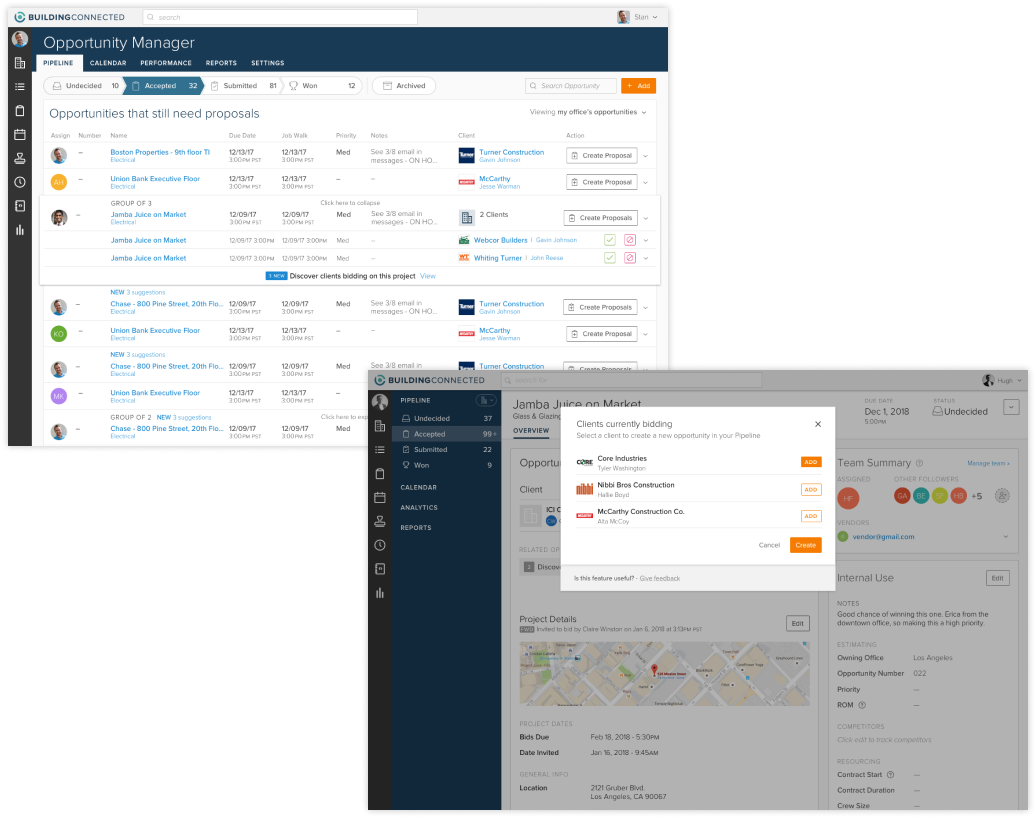

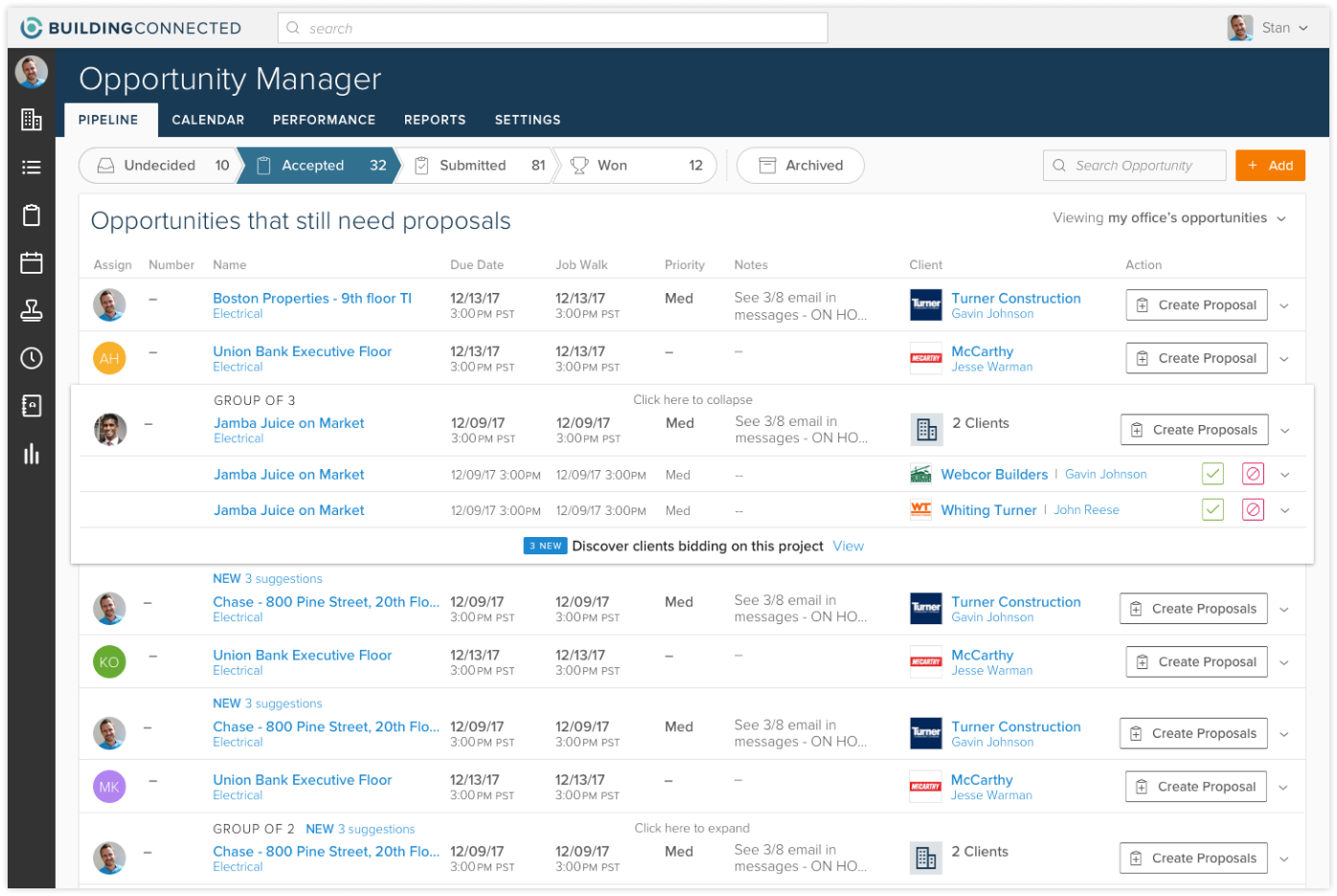

Part of the need for a quick release on our first pass was due to incoming features that would significantly change the UI we were designing for—we were going to have to redesign anyway.

For our second pass we took advantage of the richer functionality. Users now had the ability to group opportunities together. Building off of this:

- I designed calls-to-action for the inbox, allowing users to quickly scan for new suggestions

- Instead of mail-to links, I designed a quick-add feature so that users could stay in the same workflow and effortlessly begin tracking the new general contractor

Ongoing impact and learnings

Client Suggestions had a significant impact on the Bid Board product and BuildingConnected. It became a strong selling point for our Sales team and helped drive revenue until the company’s eventual acquisition.

Personally, I also learned an important lesson about about my own thinking and process. As a designer, I think there is often an urge to avoid solutions that increase “clutter”—the concern being aesthetics and scanability. However, in this case, adding more information to the already dense inbox was still the right choice. Ultimately, “clutter” must be handled holistically so that we can stay focused on the task at hand.

Morgan Keys | Summer 2019